MOTHER/SON TEAM VICTORIOUS

1251

Karakorum, Mongolia

Sorkhokhtani Beki, daughter-in-law of Genghis Khan, has shown herself to be the champion of revenge and torture, beating out her rival, Toregene.

Interested onlookers watching (from a great distance) gave her high marks for ruthlessness, efficiency, and creativity, all standard categories of the revenge/torture event in Mongolia.

But where she really racked up the points with the judges was in the Mother/Son Collaboration category. Their years of training has paid off.

She also scored high in the Plausible Deniability category. By delegating the torture and murder to underlings, she really kept her fingerprints off those weapons of torture. Smart!

The judges expect her to dominate this contest for years to come.

Who’s going to vote against her?

But seriously…

June 12, 2025

The empire Genghis Khan left when he died was fought over by his descendants in a violent and ruthless way, and the women of the family led the way in both violence and ruthlessness.

The woman who showed herself to me the most adept at these internecine war games was the wife of Genghis’s youngest son. Rashid al-Din, a Muslim visitor, called her the most intelligent woman in the world. She may also have been the most cunning.

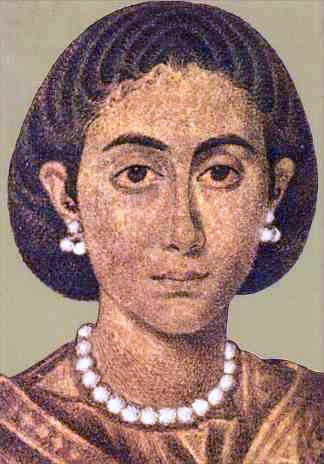

Her name was Sorkhokhtani Beki. “Beki” meant lady, and Sorkhokhtani was raised in the elite of Mongol society; her father and uncle were tribal leaders.

Her marriage was part of a political alliance. When she married Tolui, Genghis Khan’s son, her sister married Genghis. So Sorkhokhtani was both the daughter-in-law and sister-in-law of Genghis Khan.

She was a survivor. As a member of a different tribe from Genghis, she was mistrusted. Also, as a Nestorian Christian, she didn’t share the religion of her in-laws. But she ingratiated herself enough that, when the alliance that prompted her marriage fell apart, and her sister was sent packing, she was allowed to stay in the family.

Genghis Khan, as brutal as he was with enemies, protected and respected the women of his own tribe. This attitude enabled a cadre of strong women who exercised great power after his death.

The first of Toregene, the wife of Genghis’s son and successor, Ogodei.

Ogodei, as Great Khan after his father, was brutal. One day he gathered 4,000 captured girls, ages seven and up, and had them raped while the men of the captured tribe were forced to watch. He also had a drinking problem- like many Mongol leaders- and when he became incapacitated by his alcoholism, Toregene took over, effectively ruling the Mongol world. Toregene reigned from a tent made of white fabric which reputedly could hold more than two thousand men.

She presided over a reign of terror that included some devious forms of torture. She had an administrator executed by stuffing stones in his mouth until he choked to death.

The next woman in power was Fatima, a Persian captured after a battle. She may have at one time been a procuress in a bazaar.

Toregene made Fatima her right hand woman and confidant, elevating her above male administrators and even princes. She was referred to as khatun, or queen. This move, which angered the men of the kingdom. would not be forgotten.

Toregene pushed, against Ogodei’s wishes, to have their son Guyuk made Great Khan. He repaid her by having her killed, then torturing and killing her friend and confidant, Fatima. After days of publicly spectated torture, he had her orifices sewn up, bound in felt, and thrown in a river.

Ogodei had tried to marry Sorkhokhtani to Guyuk. She politely refused, claiming she needed to devote her life to her sons. Her refusal meant she could never marry again. As Guyuk’s wife, Sorkhokhtani would have been queen, but she had other plans. Long range plans. Those plans included teaching her sons to prepare to rule. She had them taught the Mongolian and Chinese languages, and power politics.

They learned their lessons well.

Mongke, like his mother, was patient and sober. He was the first non-alcoholic khan since Genghis.

The next woman to rule was Guyuk’s widow, Oghul Ghaimish. She was power-hungry and ambitious. She once demanded of an emissary of King Louis IX of France, that he come to Mongolia and surrender to her. But Orhul was more greedy than clever; she raised taxes on the poor. Like Toregene, she alienated the people whose support she most needed.

In 1251 Sorkhokhtani showed her political acumen by persuading the Mongol men to call a khuriltai, or parliament, for the purpose of electing a new Great Khan. She then maneuvered to get her son Mongke the needed support. Her plan worked. Her son was not the leader of the Mongols.

The first order of business was revenge. It started with a cabal of princes who had planned to kill Mongke on the day of his coronation. After executing them, Sorkhokhtani found their mothers, and had them killed also.

Mongke had a problem. Genghis had made it a crime to execute anyone in the Borijin clan. This rule had helped them remain as a cohesive unit, avoiding infighting. The khans and their wives before him had disregarded this law, and had engendered the resentment of the clan. Mongke wanted to insulate himself from blame, so he hired a man named Menggeser Noyan, who was of another clan, and made him a judge. This man carried out the brutality for Mongke, who was technically not breaking the law.

But for all of her planning and patience and discretion, Sorkhokhtani couldn’t keep the torture from becoming more and more sadistic. Revenge begets revenge, and torture added to torture. One of Mongke’s wives hired a brother and sister team to execute one of her enemies, without telling her husband. He had the brother decapitated, then had his head hung around the neck of the sister and had her paraded through camp before killing her. Another woman was killed by having her limbs kicked to a pulp.

Sorkhokhtani at this point became ill, and, apparently fearing for the welfare of her eternal soul, stopped the torture and the killing. But she still wanted to send a message, so had her enemies sent as soldiers to the hottest battle spots, or on embassies to the most dangerous peoples. She also had all their families and goods distributed to her friends. She was more careful and maybe more humane than her predecessors, but it was still the thirteenth century, and she still had a job to do.

Sorkhokhtani succeeded where the other women failed, by teaching her sons carefully enough that they didn’t kill her. In the brutal world of Mongol dynastic succession, that was an achievement. She died a peaceful death, knowing that her son was still in charge.

Another son, Kublai, would one day rule China, even setting up his own dynasty there. Luckily for her, she didn’t live long enough to see Kublai murder his brother, Arik Boke, in the next round of succession slaughter.

So much for enlightenment.

Sources

The Secret History of the Mongol Queens, How the Daughters of Genghis Khan Rescued His Empire, Jack Weatherford

Genghis Khan, His Conquest, His Empire, His Legacy, Frank McLynn